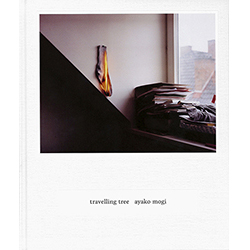

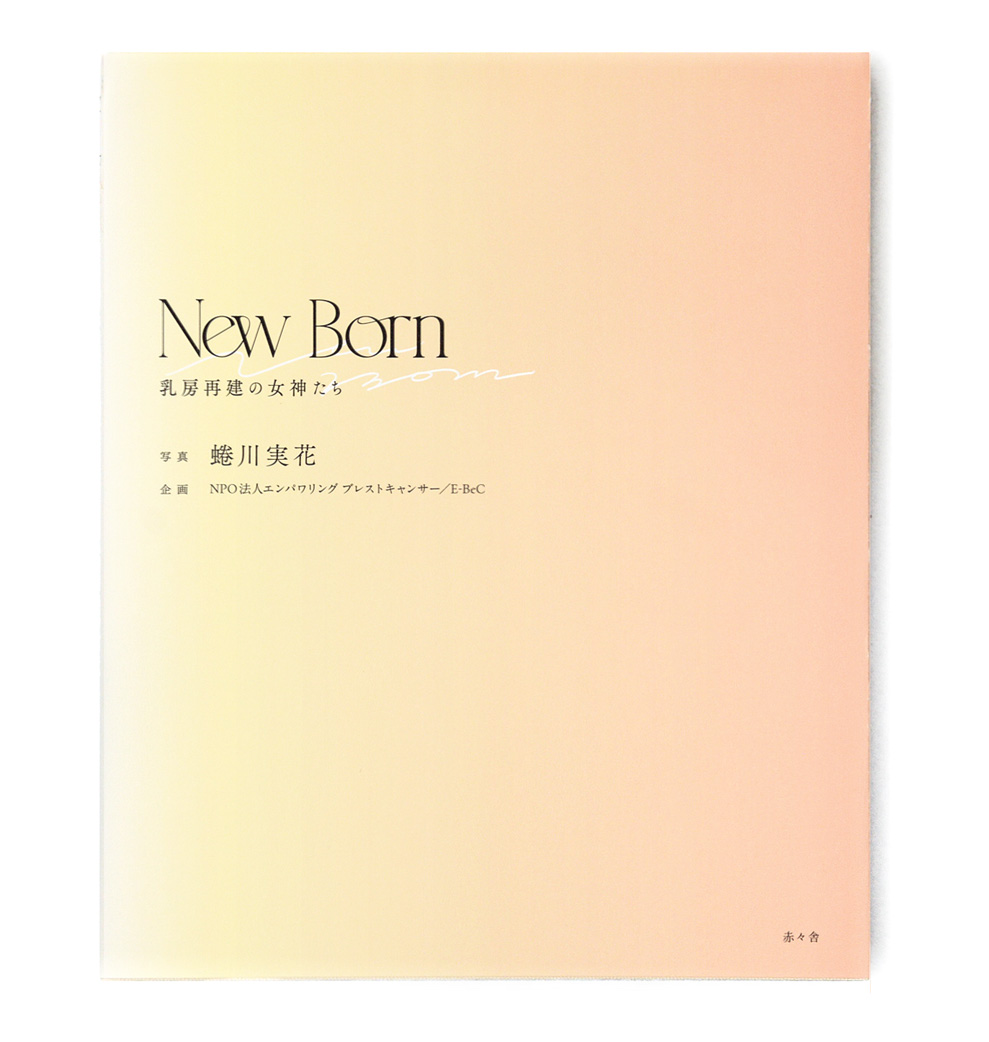

『New Born ー乳房再建の女神たちー』

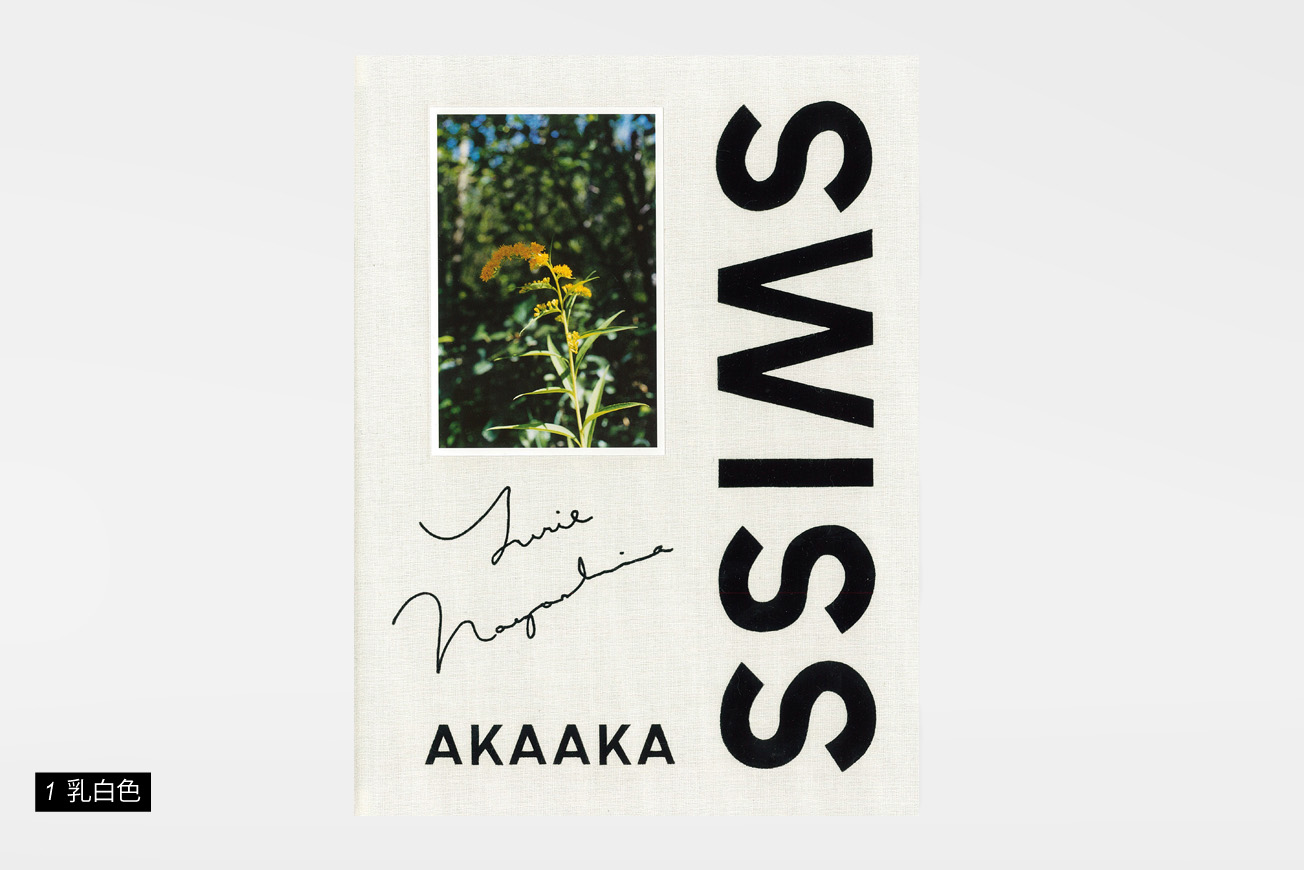

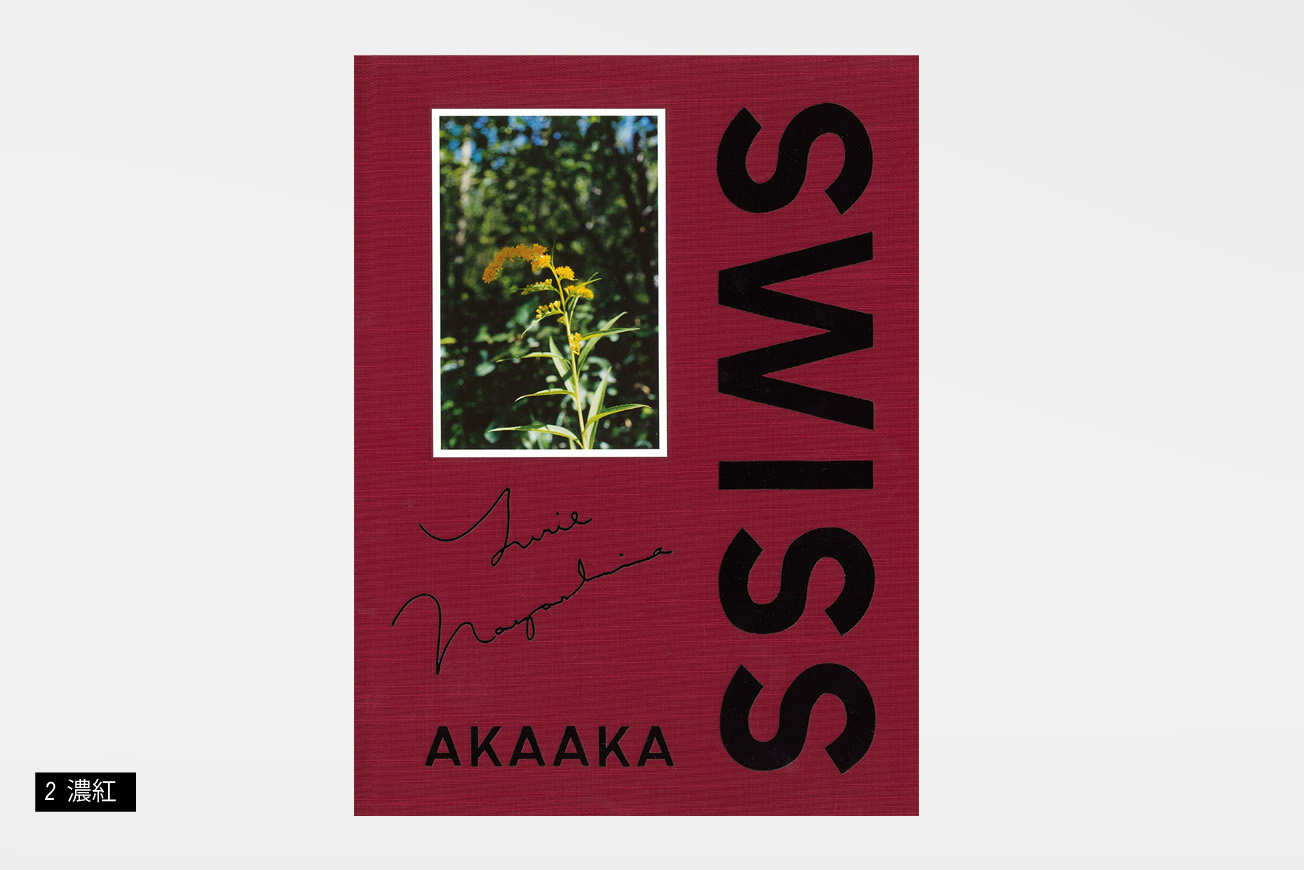

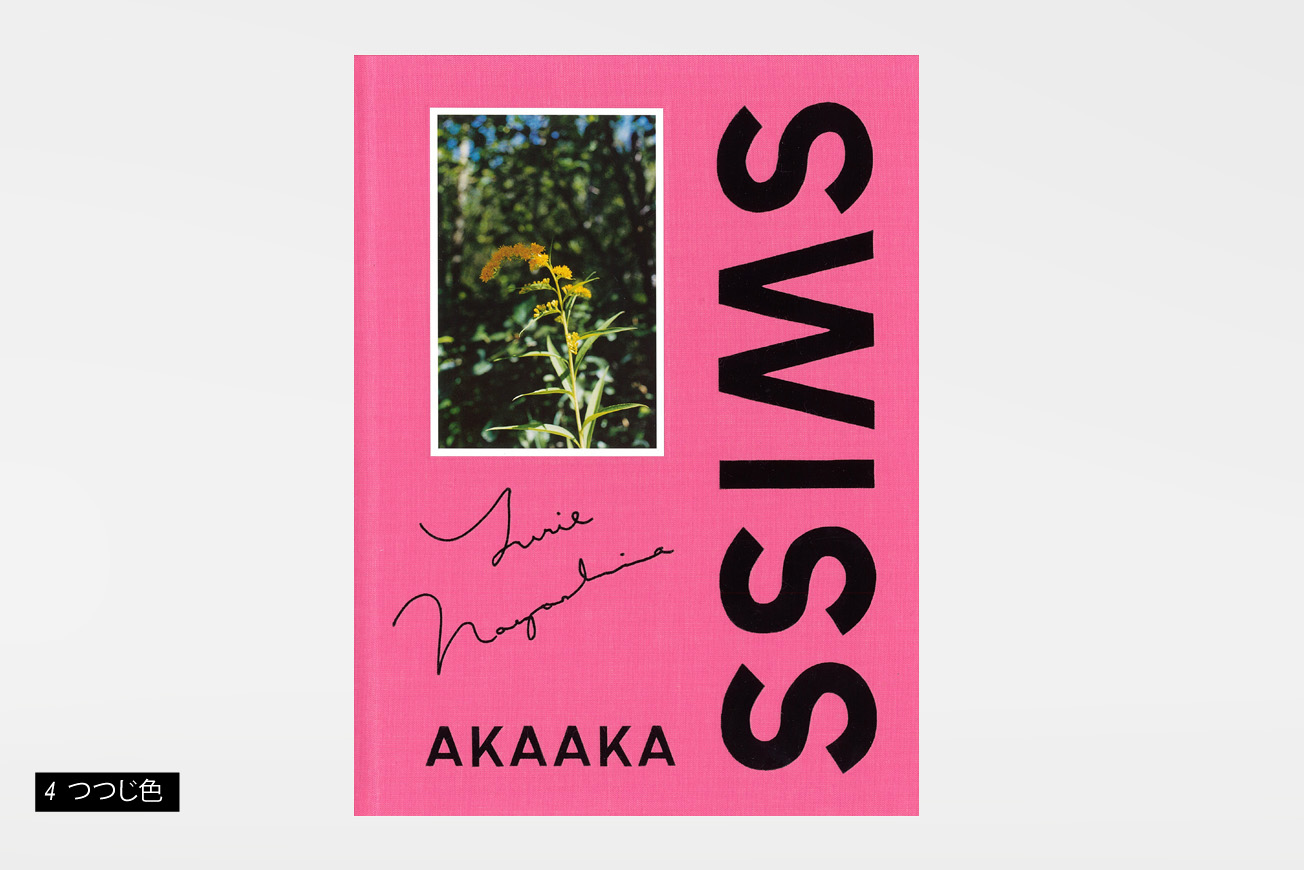

Book Design:脇田あすか 企画 : NPO法人E-BeC 発行:赤々舎 Size:H225mm × W188mm Page:88 pages(カラー写真) Binding:Softcover Published in October 2024 ISBN:978-4-86541-189-8 |

¥ 2,700+tax

国内送料無料! お支払い方法は、PayPal、PayPay、Paidy 銀行振込、郵便振替、クレジットカード支払いよりお選び頂けます。 |

|---|

About Book

乳がんを経験し、

乳房再建をした12人の写真とメッセージ

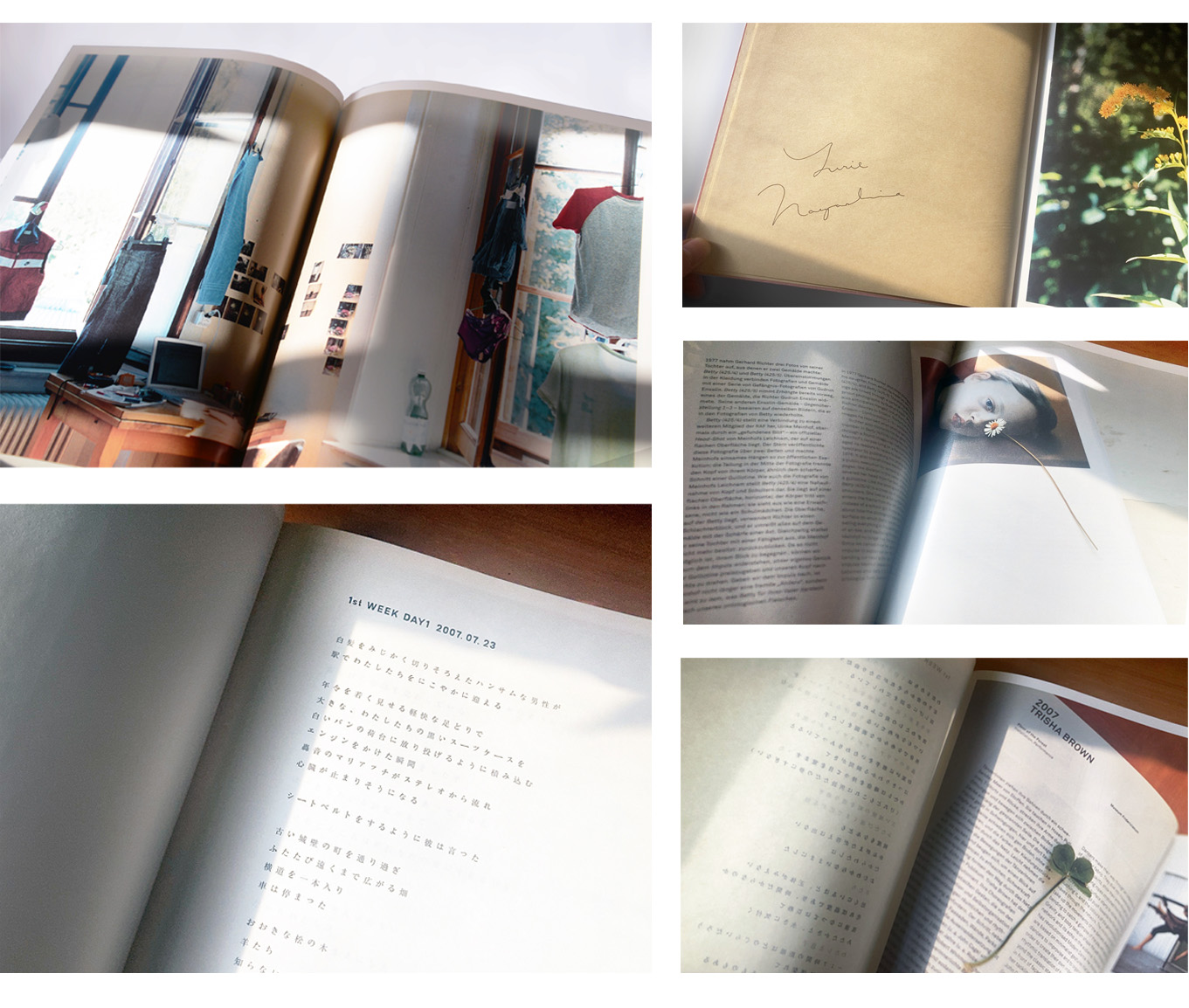

企画は、「乳房再建手術」の正しい理解と乳がん患者さんのQOL向上を目指して2013年より活動する「NPO法人 E-BeC」(前身母体:STPプロジェクト)によるもので、2010年に、前作『いのちの乳房~乳がんによる「乳房再建手術」にのぞんだ19人~』を刊行しています。

当時はまだ再建手術のできる施設が限られていましたが、出版後「写真集を見て勇気づけられた」「再建のことを知り前向きに治療を受けることができた」など多くの声を頂き、刊行から13年が経ち完売となった今も「写真集を手にしたい」という声を多く頂いています。

New Born

Photo by Mika Ninagawa, Planning by Mika Masui (Nonprofit Organization E-BeC)

This is the second photobook from E-BeC featuring women who have undergone breast reconstruction surgery.

The first photobook was published in 2010 by the STP Project, the predecessor of E-BeC.

There was not much information about breast reconstruction surgery at that time. The photobook was conceived from the desire to make it more generally known, so 19 women including myself who had experienced breast reconstruction became models and shared our stories.

Fourteen years have passed since then.

The number of breast cancer patients increases every year and various treatments for breast cancer and methods for breast reconstruction continue to evolve.

Unfortunately, with respect to breast reconstruction surgery, the same cannot be said for the environment surrounding patients, which has not changed much at all.

What we feel on a daily basis through our E-BeC activities is the large regional disparity in the information that is available.

In the Tokyo Metropolitan Area, the flood of information and number of options leaves many patients troubled as to what to decide on and what to base their decision on.

Contrastingly, women living in areas removed from major cities haven't heard about breast reconstruction surgery. Even if they do know about it, they may not know where they can have the procedure done or what types of surgery are available and so they give up or are unable to opt for the surgical method they want. Some patients cannot go ahead with surgery due to opposition from the people around them. I've also heard that there are more women than you would imagine who don't have surgery because they don't know of anyone else who has had reconstruction and they don't fully understand what it involves.

We have decided to publish this second photobook from the desire to let as many women as possible know about breast reconstruction surgery and understand what it involves.

When you are not in a condition to be able to assess things calmly and logically, it is very difficult to gather the information necessary. This was also my experience. In those circumstances, the doctor told me about breast reconstruction surgery, which was not typical at the time, and that helped me to be able to move forward.

Our aim for this second photobook is to provide encouragement to breast cancer patients who feel as if their heart is breaking and to many other women as well.

"Mika Ninagawa is the only one who can truly capture our message in photographs!" I thought. In a leap of faith, I asked if she would consent to take the photographs and she graciously accepted.

More than 80 women applied to be models, which far exceeded our expectations. It must have been a big decision to show people a breast with a surgical scar. We selected 12 women who expressed desires such as to be photographed by Mika Ninagawa, to let more women know about breast reconstruction surgery, or to do something to help fellow breast cancer patients.

In recent years, breast reconstruction surgery has come to be perceived as part of taking care of changes to appearance caused by cancer treatment the same way as caring for one's appearance with wigs, makeup, and nail care. As with other kinds of care, it is up to the patient to decide whether or not to have reconstruction done. But not having surgery because you don't know about breast reconstruction and choosing not to have surgery based on knowledge of it are two entirely different things with different effects on a woman's mental and emotional quality of life.

E-BeC aspires to a society in which anyone anywhere can receive breast reconstruction surgery that meets a certain standard if that is what they desire. If this photobook is successful in stimulating interest in breast reconstruction surgery and providing an opportunity for women to obtain accurate information about it, then there is nothing that could bring us greater happiness.

Excerpts from the forewords

Nonprofit Organization Empowering Breast Cancer / E-BeC

Mika Masui, Director

When I was approached to take the photographs for this photobook, I immediately accepted with the feeling that I wanted to do whatever I could to help. There is nothing that gives me greater happiness than being able to give even a little encouragement to someone move forward.

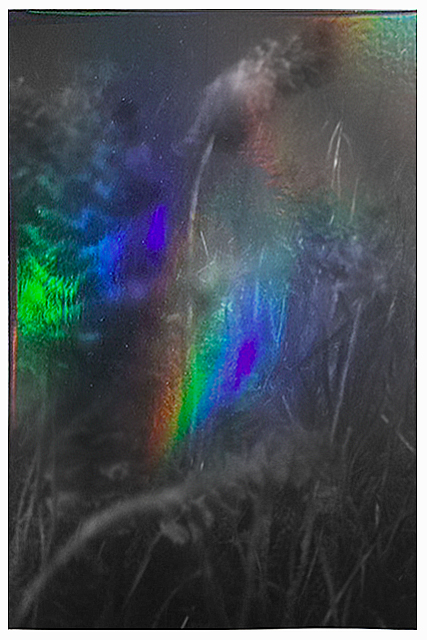

I wanted to create photographs that radiate an absolute sense of happiness. I approached the work with the desire to keep the focus away from the troubling and painful experiences the models had gone through and instead celebrate the shining "Now" that is possible exactly because they had endured and overcome those experiences.

Compared to a typical photoshoot, I planned a more relaxed schedule because I wanted to have enough time to genuinely engage with each model to be able to draw out the best in each one. Together with hair and make up staff, we worked as one team to help the models feel more confident and elicit even more self-love, and we concentrated on discovering and amplifying each woman's unique beauty.

All of the models got a direct feel for the radiance they embodied and translated it into strength that they projected outwardly to a degree above and beyond our expectations. I and all of the staff members were energized by that strength. It is my hope that the photographs will convey this beautiful positivity to everyone who views the photobook.

In conclusion, what was wonderful about this project to me was that it wasn't trying to promote breast reconstruction but rather to be a photobook that provides a source of information for women contemplating breast reconstruction that can assist them in making an informed decision. Through the models' photographs and their accounts of their experiences, people can learn about methods of breast reconstruction that are available as well as something about the lives of women with actual experience of breast cancer and breast reconstruction. If this photobook leaves readers with a more optimistic outlook than they had before encountering it, then that gives me much joy.

from the afterwords

Mika Ninagawa 《Photographs That Celebrate a Shining "Now" 》

Artist Information

写真:蜷川実花

写真家、映画監督。写真を中心に、映画、映像、空間インスタレーションも多く手掛ける。クリエイティブチーム「EiM」の一員としても活動。 木村伊兵衛写真賞ほか数々受賞。『ヘルタ ースケルター』(2012)はじめ長編映画を5 作、Netflix『FOLLOWERS』を監督。最新写真集に『花、瞬く光』。個展「蜷川実花展 : Eternity in a Moment 瞬きの中の永遠」(TOKYO NODE 2023年12月 ー 2024年 2月)にて 25 万人を動員。 https://mikaninagawa.com

Photo by Mika Ninagawa

Photographer, Film Director

Mika Ninagawa works mainly in photography, but also in film, video, and spatial installations. She is also a member of the creative team "EiM."

Recipient of numerous awards including the Kimura Ihei Photography Award. She has directed five feature films, including Helter Skelter (2012), and the Netflix original drama FOLLOWERS. Her latest book of photography is "Flowers," Shimmering Light. Visitors of her solo exhibition "Mika Ninagawa: Eternity in a Moment" (TOKYO NODE, December 2023-February 2024) were over 250,000.

企画:NPO法人 E-BeC

乳がん患者さんが、乳房再建手術について正しい情報 を得たうえで、自ら再建手術をするかしないかを選択し、 希望する誰もが一定水準の再建手術を受けられる社会を目指して活動している。https://www.e-bec.com/

Planning by E-BeC

The nonprofit organization Empowering Breast Cancer/ E-BeC works toward development of a society in which breast cancer patients have accurate information concerning breast reconstruction surgery that enables them to make an informed choice about whether or not to undergo reconstruction surgery so that anyone who desires reconstruction has access to reconstruction surgery that meets a certain standard.