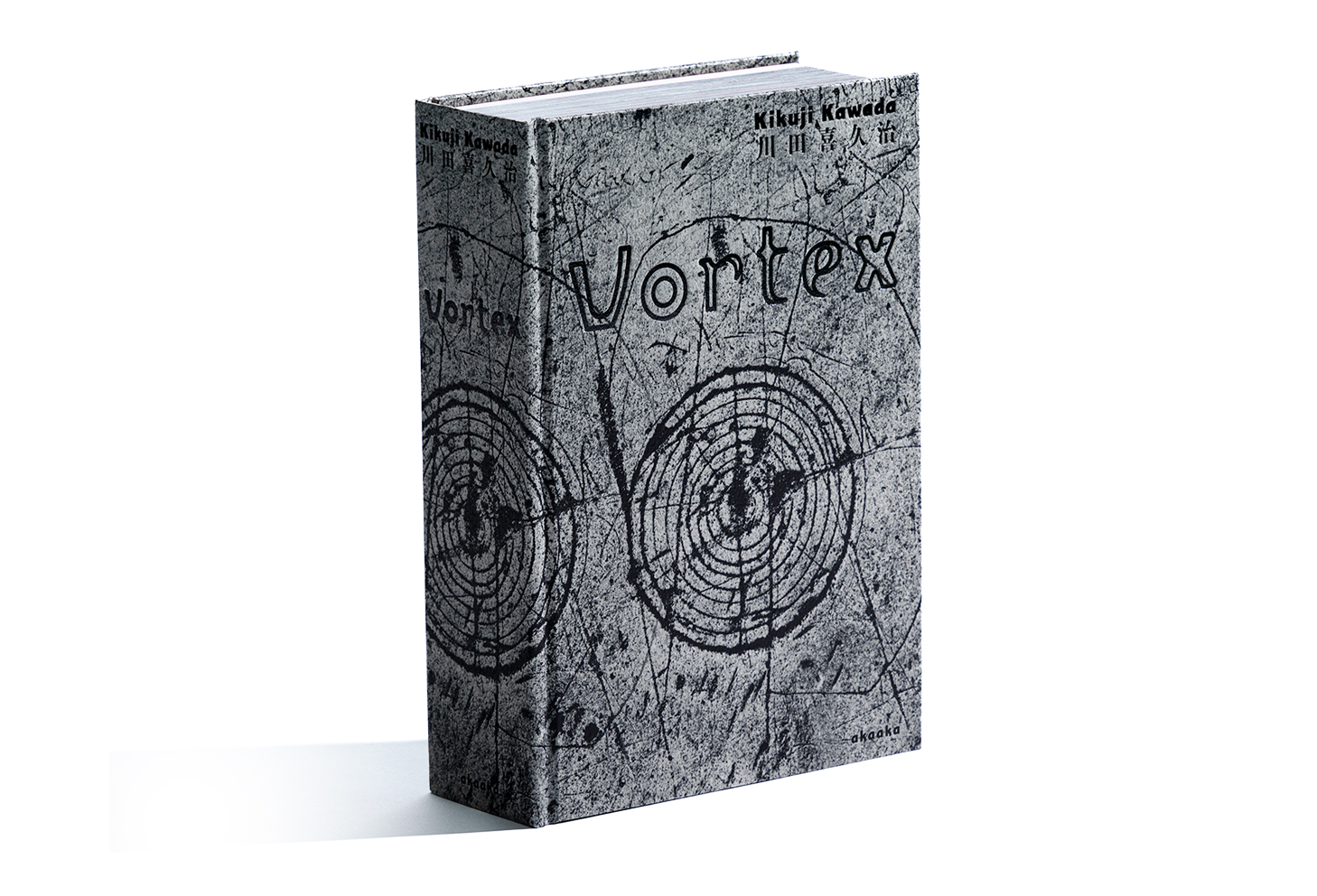

川田 喜久治『Vortex』

発行:赤々舎 Size: H216mm × W154mm Page:544 pages Binding:Hardcover Published in July 2022 ISBN:978-4-86541-149-2 |

¥ 8,000+tax

国内送料無料!

|

|---|

About Book

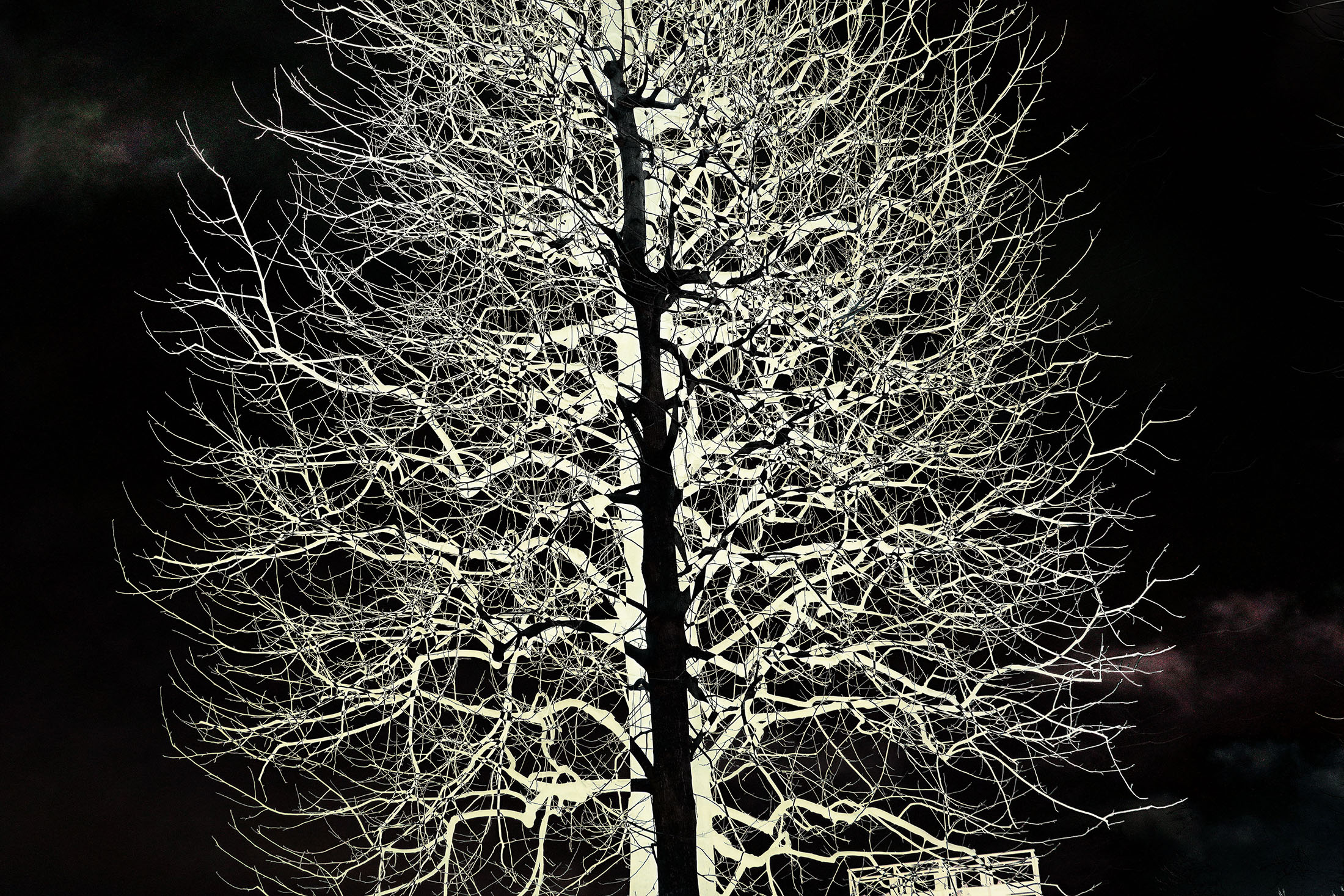

都市に氾濫する万物をないまぜにしながら螺旋の底へと消え、光る

|

編集 |

|---|

Vortex

Kikuji Kawada

On September 5th, 2018, in one of his early Instagram posts, Kikuji Kawada shared a photograph of a poster that read: "Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt."1 This quote, by Kurt Vonnegut, is extracted from his masterpiece Slaughterhouse-Five, praised as "one of the most enduring antiwar novels of all time."2, 3 Vonnegut, an American novelist born of German parents, enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II, in 1943, when he was 21 years old. Captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge, he was taken as a prisoner of war in Dresden, where he survived the Allied bombing in a meat locker of the slaughterhouse where he was detained. This experience provided the traumatic substance of his novel, but also the somewhat comedic undertone of the style that he came to be known for. His work became an emblem of American post-war counterculture. It seems quite fitting that Kawada would pick Vonnegut's words and make them his own through the prism of social media. He tagged this post with "#kurtvonnegutjr," "#スローターハウス5" and "# なにもかもうつくしく" : "Everything is beautiful." A few hours later, that same day, he posted another photograph: rows of cars in flames in the aftermath of a typhoon, as seen in the news, on a TV screen. The poetic irony of this sequence echoes Vonnegut's quote, and Kawada's entire oeuvre, starting with Chizu (The Map). [...]

Like Vonnegut, Kawada uses his art to sublimate a pain that is profound, and indescribable. In his photographs, everything is beautiful because it hurt. What remains from insane, natural or manmade destruction, is only made beautiful through the eye of the artist that transcends it. Kawada's more recent work, be it "The Last Cosmology", "Los Caprichos" or his latest photographs, published in this book, seems to be a prolongation of this epiphany: as if he needed to go back to this moment, as if it had become an obsession.

In the history of Japanese photography and in the history of photography at large, Kawada stands out. An iconoclast and a self-admitted contrarian, he offers a vision of the world that is personal, spiritual, and elevated. To photo historian Ryuichi Kaneko, he once jokingly told an anecdote about Yukio Mishima's perplexed reaction to Chizu: "I overheard him asking, 'What kind of 'stains' are these? Stains left by what?' I was a bit contrary back then, you know. I said, 'That's for you to imagine, sir'."6

His work is for us all to imagine: Kawada always steered clear of the literal. This may be in part because a literal narrative form would not allow him to express the weight of his experience. Writing about Belgian photographer Anton Kusters's work on the memory of the concentration camps, photography historian Fred Ritchin explained: "The German novelist W. G. Sebald felt that 'the recent history of his country could not be written about directly, could not be approached head-on, as it were, because the enormity of its horrors paralyzed our ability to think about them morally and rationally,' as Mark O'Connell wrote in the The New Yorker on the tenth anniversary of Sebald's death. 'These horrors had to be approached obliquely.'"7

This seems to be Kawada's approach: an oblique way of telling the story, and blending the genres. A tongue-in-cheek approach to the gravity and the seriousness of our condition -the coping mechanism of the traumatized. His existential irreverence is in no small part what draws us into his universe, and what makes him stand out.

Kawada's work could be defined as layered documentary. He explains: "An image taken of the 'present,' whenever that is, is so strong--vivid in hue, aspect, substance--because it's a document. I seek even now to explore new forms for documentary to take. When you layer things in the way we've been discussing, the layers produce meaning, metaphors emerge as you go deeper into the juxtapositions that arise, and the ways of seeing the image multiply."8[...]

With Covid-19, reality started to look more and more like fiction. The masks that Kawada used in his "Los Caprichos" series, his masterful tribute to Goya's eponymous social fables, made over 40 years ago, took a deeper meaning. On October 16th, 17th, and 18th in 2021, he posted a series of photographs that hinted at his eerie prescience. In a personal essay he wrote in 2016, published in Remote Past a Memoir: 1951-1966, Kawada recalled a traumatic brain surgery: "I was desperate to recollect my memories from a mere few hours ago. Being in this dark place had brought more fear upon me than the thought of brain surgery. After a while my memories came back to me in a trembling surge. Suddenly, I saw an array of photographic negatives floating before my eyes. In pursuing these images where light and darkness were reversed, I had found myself lost and unable to distinguish between past and future..."16

This is the emotion that he masterfully channels and makes visible in his photographs: negative turned positive, positive turned negative. His disturbing and ominous images are a place of excavation, of traumas either lived or foreseen. The world they describe - his world, Tokyo - appears like Dante's Inferno, both flooded and in flames. By combining vivid colors that range from burning flames to ice blue, by playing with contrasts and textures, Kawada generates a series of fantasies, a world that is perpetually at war, but still standing. In that same essay, he writes: "It is by no means an overstatement to say that all I can remember from my memories extending across the distant horizon are places of ruin and chaos... The catastrophe of the 100 Suns and the fear of cesium remain still lurking in our future skies. The conversation between father and daughter continues to be repeated like a spell of sorts, 'You know daddy, the world is going to end tomorrow.' 'What, the world will end tomorrow?'" Looking at his photographs,we don't know if we are witnessing the end or the beginning of the world.17

Kawada's vision is that of a man who has confronted death repeatedly and remained on the side of life. It is at once obscured and illuminated. Vonnegut ended the long letter that detailed his wartime experience as a prisoner by saying: "I've too damned much to say."18 In his work, Kawada, too, grapples with the desire to say it all, through photography. [...]

After countless hours spent getting lost in Kawada's Instagram stream of consciousness, being all consumed by it, one feels as if they've had a timeless conversation with a man of outstanding depth, soul, and modernity. Bringing the past into the present, in the immense chaos that we are experiencing, his photographs tell us that he is, and that we are, and that the world is, still very much alive. In all the madness to be seen, through all the dark clouds, Kawada shows us that there is still some light.

Extracted from the text

"Everything was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt On Kikuji Kawada's Illuminating Contemplations"

Pauline Vermare

Related Exhibiton

川田喜久治 「ロス・カプリチョス 遠近」 会期:2022年6月29日(水)〜8月10日(水) 時間:11:00〜18:00 会場:PGI (東京都港区東麻布2-3-4 TKBビル3F) 定休日:日曜・祝日 |

Artist Information

川田 喜久治

1933年 茨城県生まれ。 1955年、新潮社に入社。1959年に新潮社を退社しフリーランスとなる。佐藤明、丹野章、東松照明、奈良原一高、細江英公と共に写真エージェンシー「VIVO」 (1959-61年)を設立。

敗戦という歴史の記憶を記号化するメタファーに満ちた作品集『地図』を 1965年に発表し、以来現在に至るまで、常に予兆に満ちた硬質で新しいイメージを表現し続けている。

自身の作品を「時代の中の特徴的なシーンと自分との関係をとらえて表現し、その時の可能な形でまとめ上げ、その積み重ねから一つのスタイルが生まれてくる」と語る。近年はInstagramにて写真への思考を巡らせながら、日々作品をアップロードし続けている。

Kikuji Kawada

Born in Ibaraki, Japan in 1933. He joined Shinchosha in 1955. He became a freelance photographer and co-founded the VIVO collective in 1959 together with Akira Sato, Akira Tanno, Shomei Tomatsu, Ikko Narahara and Eikoh Hosoe.

In 1965 he released The Map, a groundbreaking photobook loaded with postwar political metaphor, and he continues to challenge our intellect with similarly fresh and clairvoyant im- ages to this day. Kawada describes his work as "an expression of a specific scene in time and my relationship to it, framed accordingly, and the style born from the exchange." These days Kawada can be found posting images and photographic musings to his Instagram account.